:background_color(FFFFFF):format(jpeg)/images/library/13435/Ca4EPJ42qNOFSNQadWUcyQ_A._iliaca_communis_m01.png) Common iliac artery: Anatomy, branches, supply | Kenhub

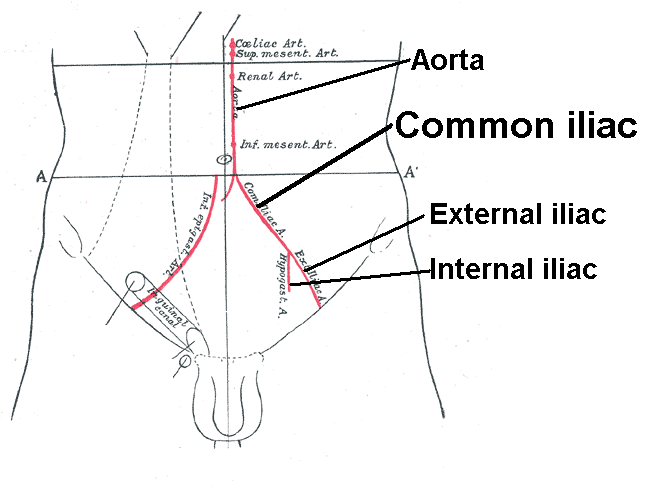

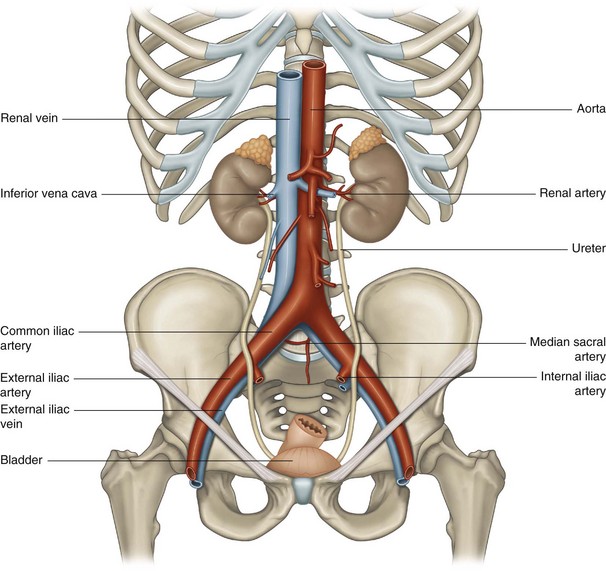

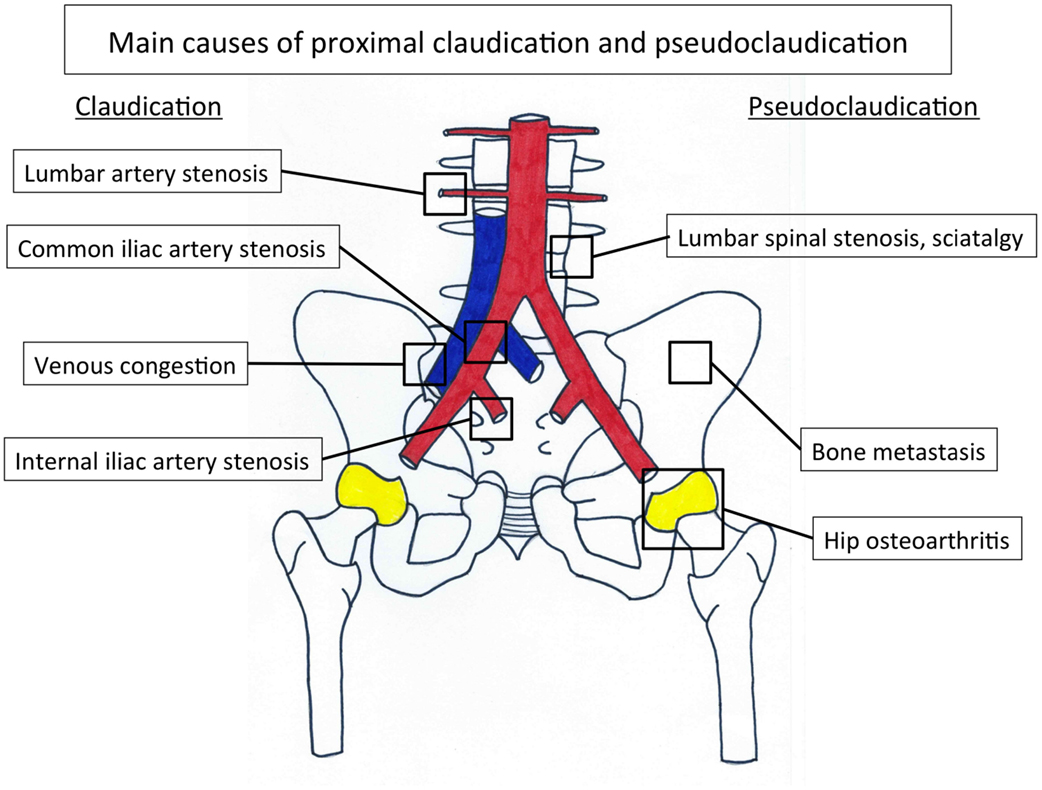

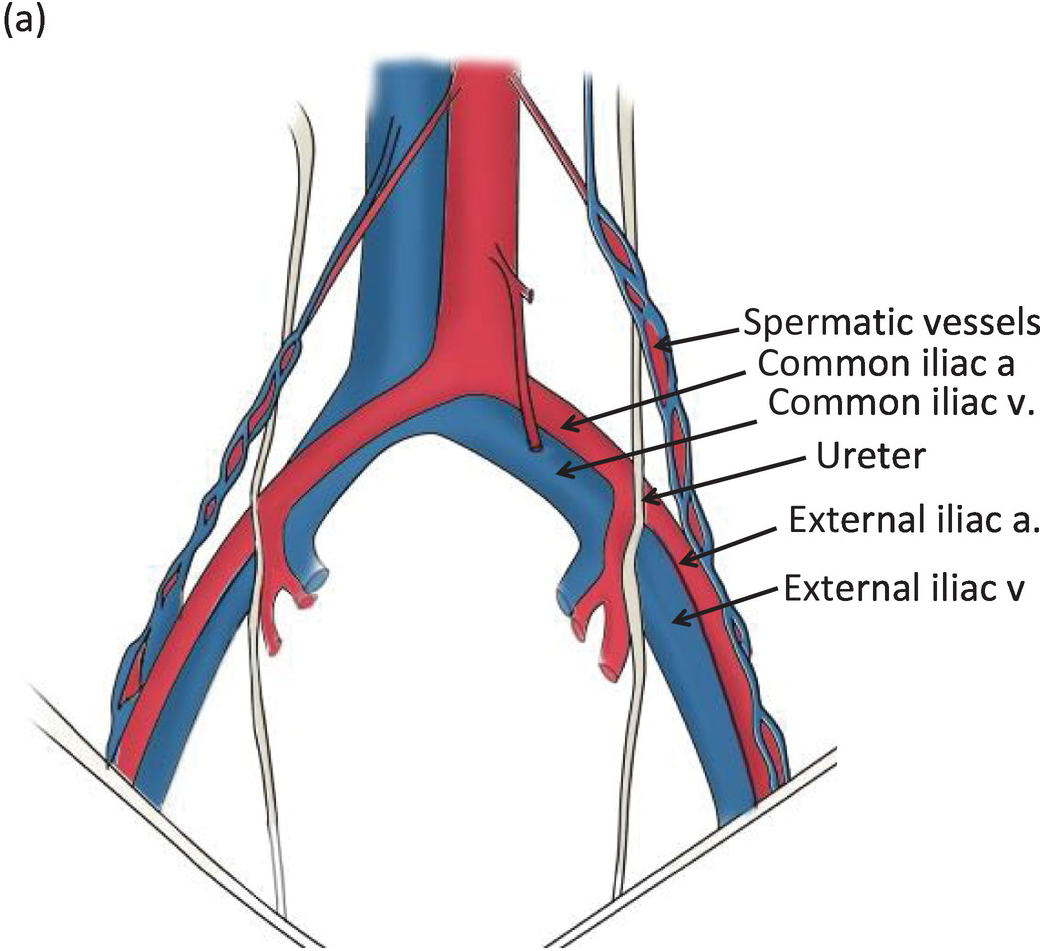

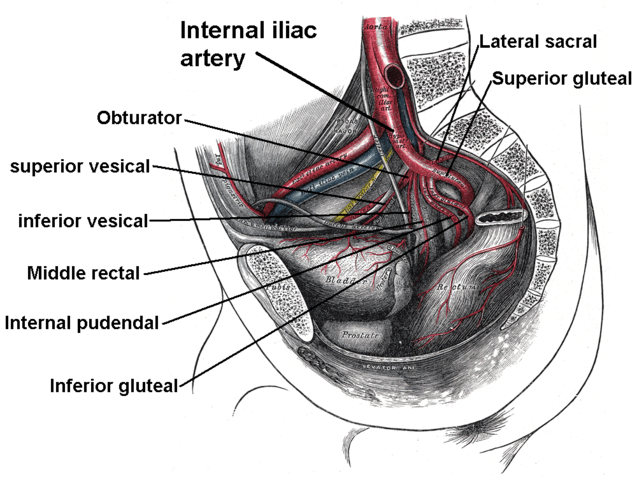

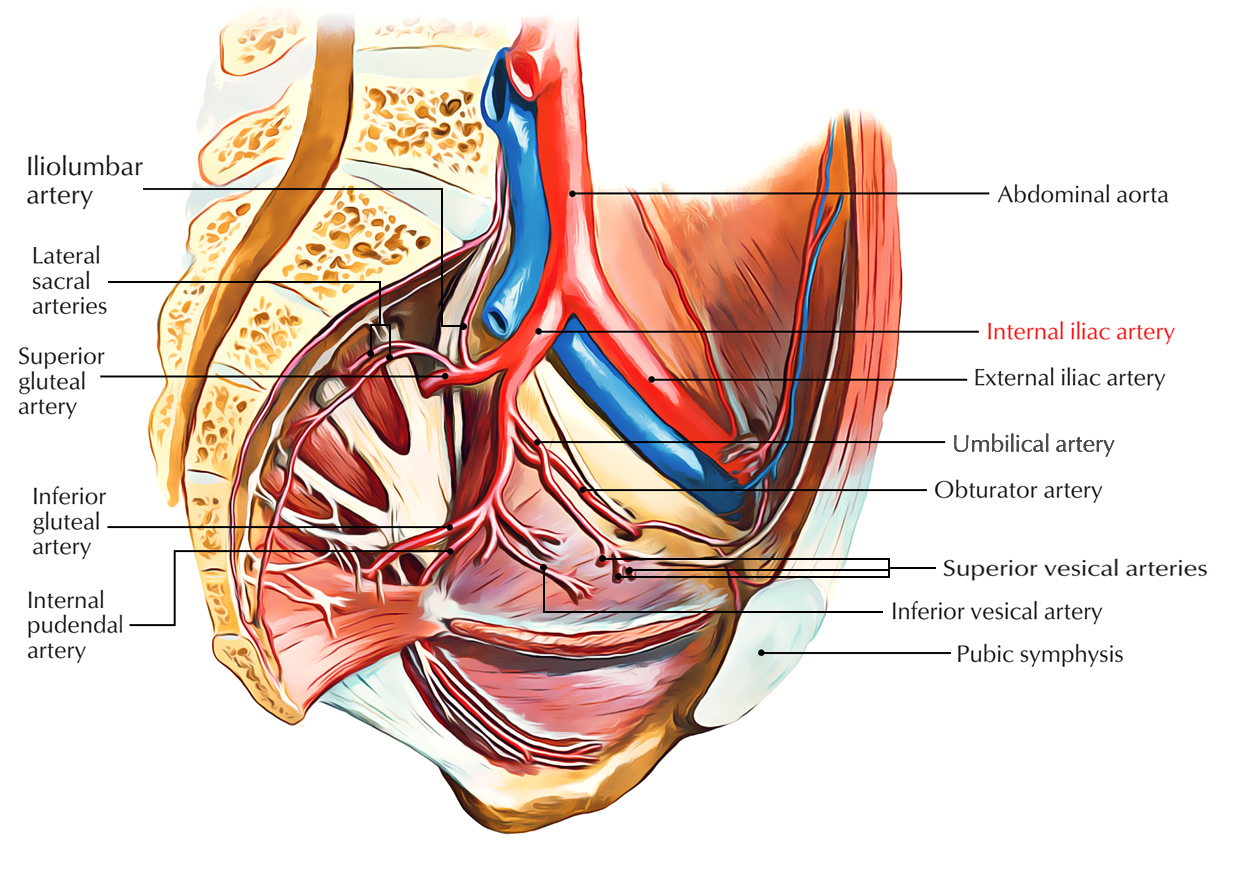

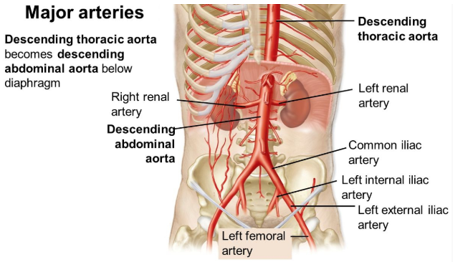

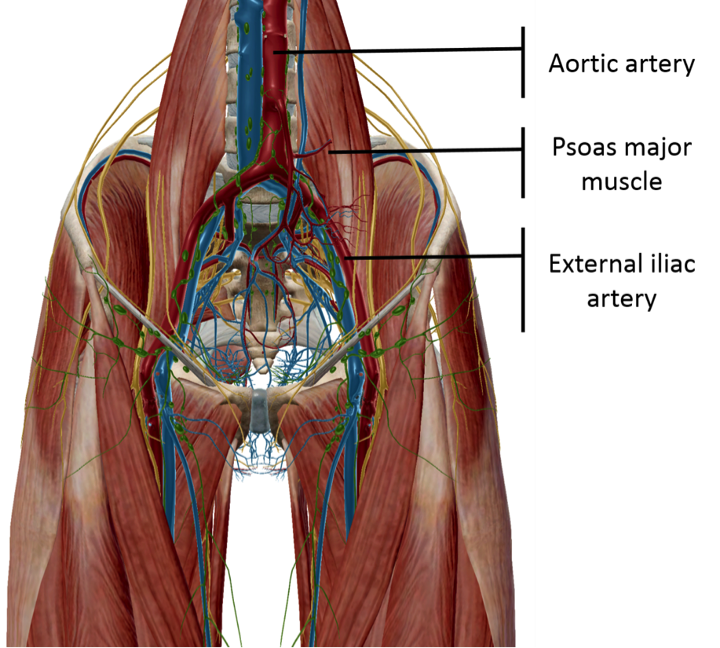

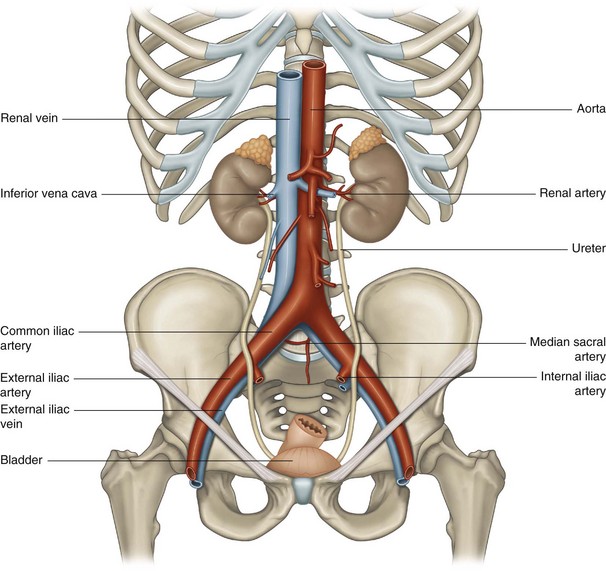

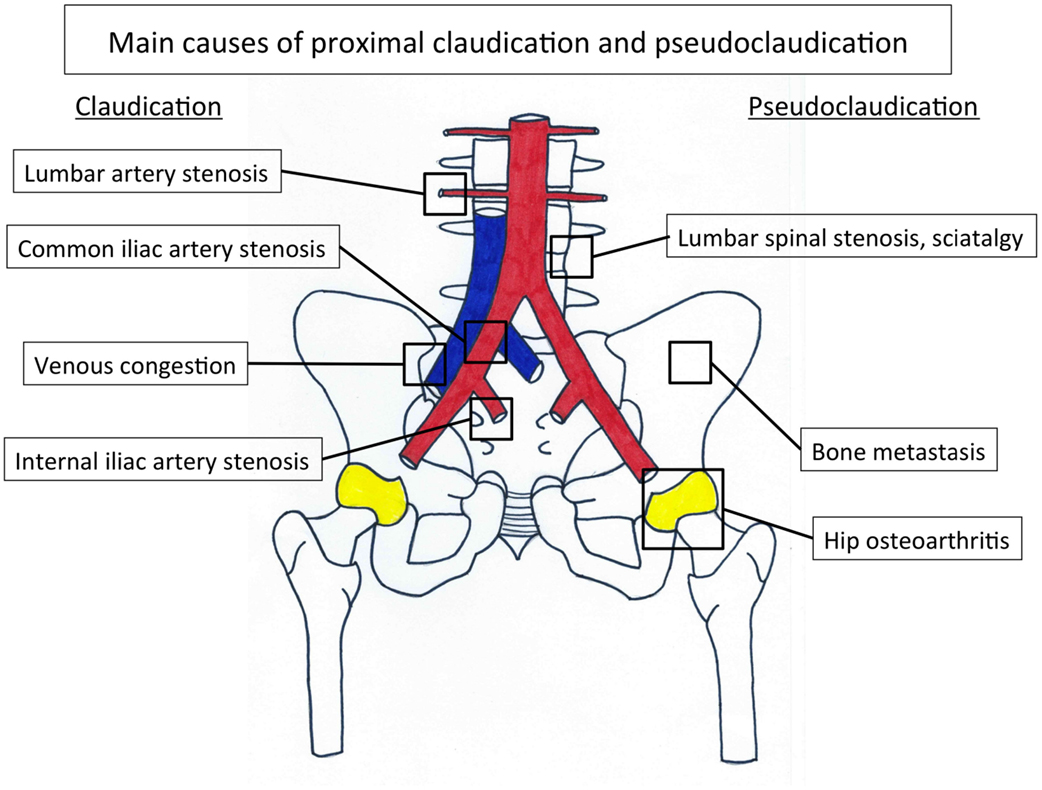

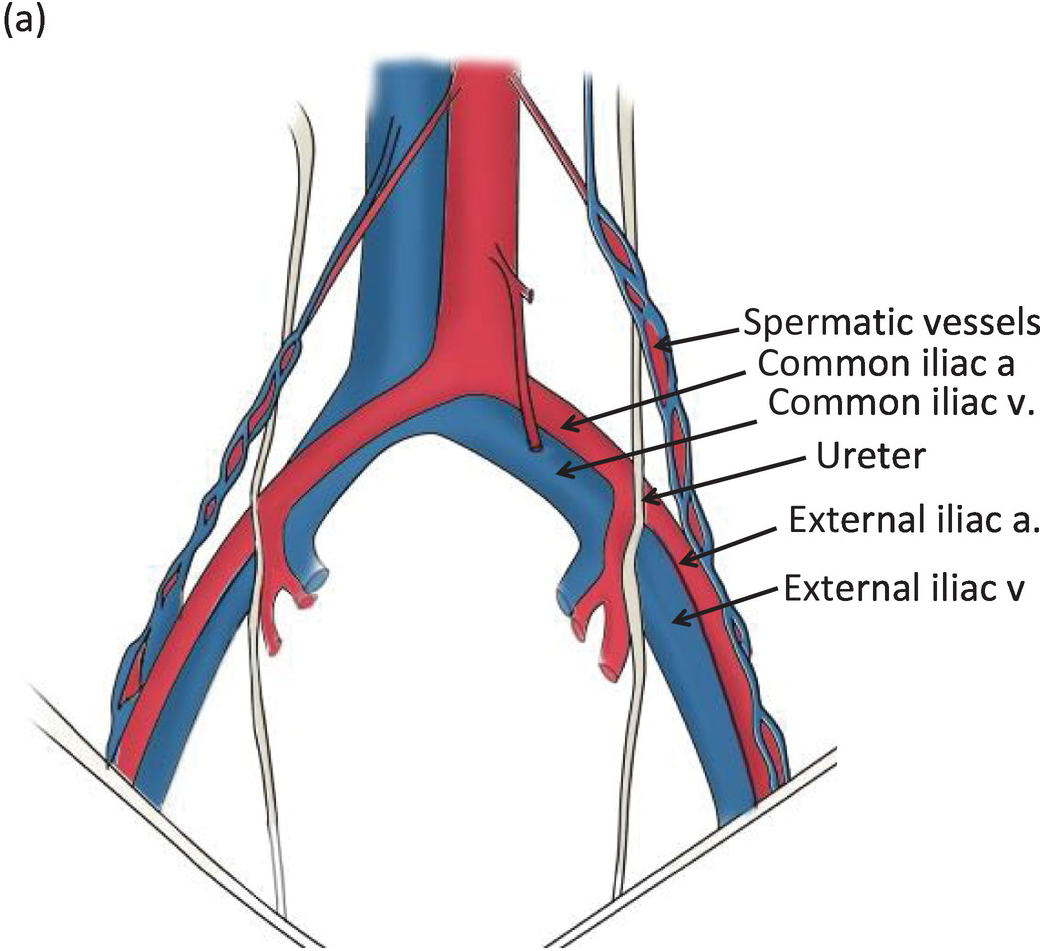

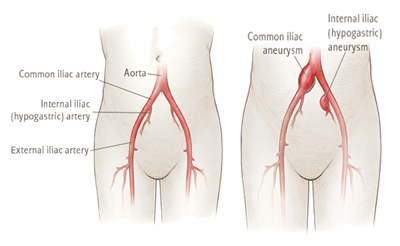

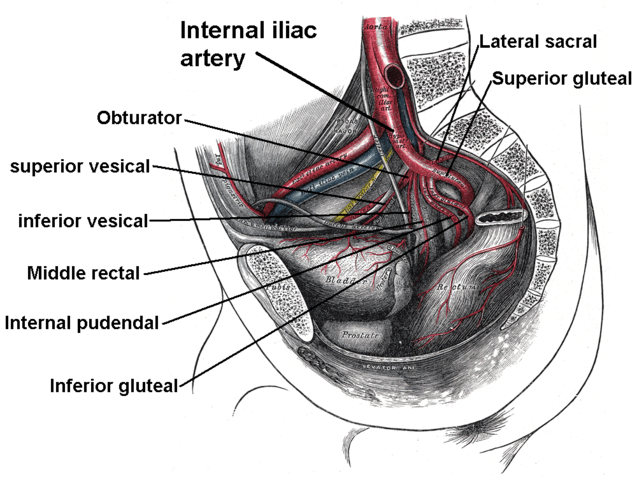

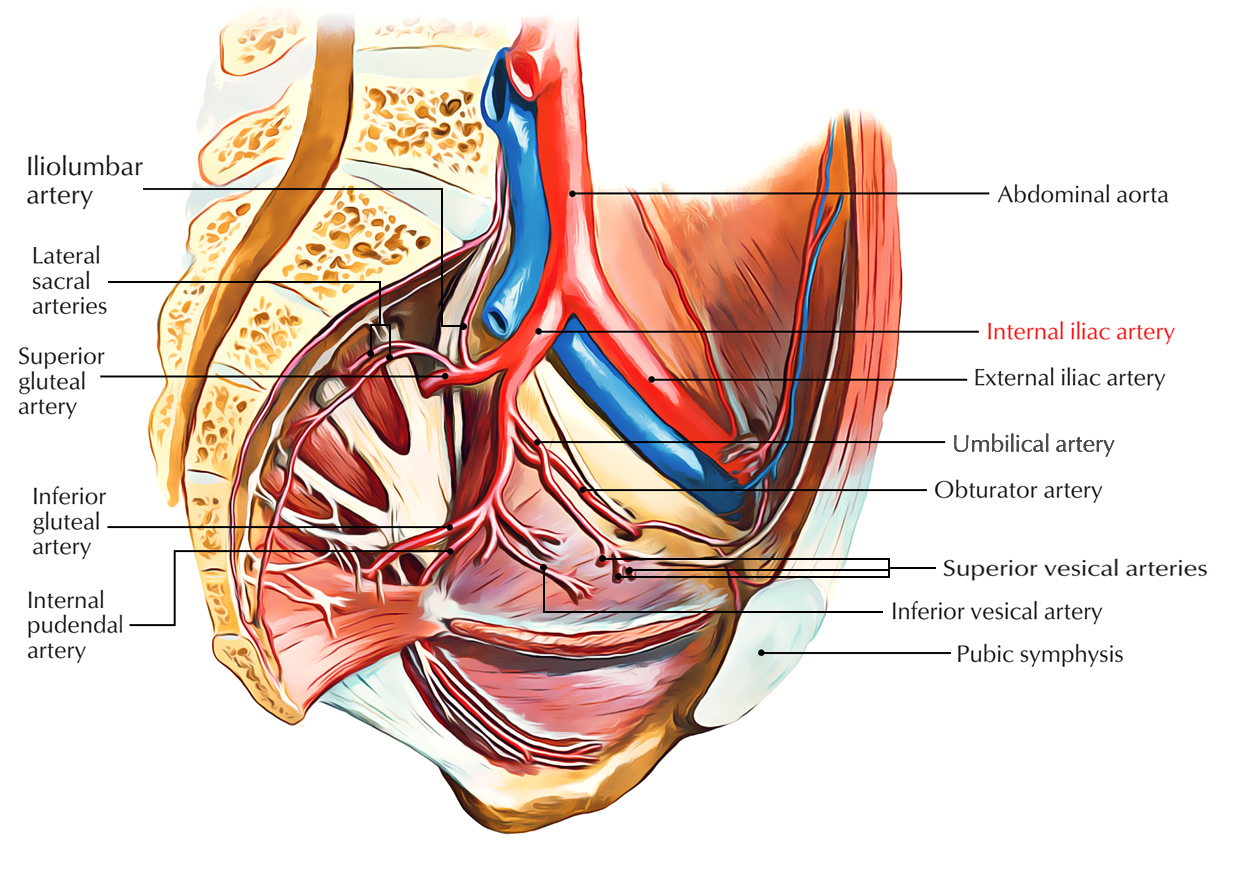

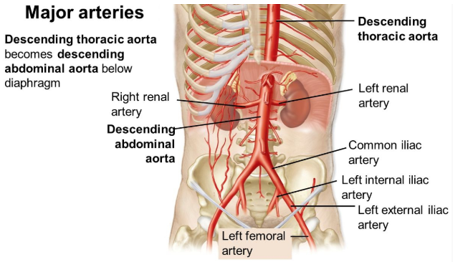

Common iliac artery: Anatomy, branches, supply | KenhubImpact factor 3.915 Silence CiteScore 3.7More on impact › Article Internal iliac arterial stenosis: diagnosis and how to manage it in 2015The lower extremity (LEAD) arterial disease is a highly prevalent disease that affects 202 million people worldwide. The stenosis of the inner iliac artery (IIAS) is one of the LEAD locations. This diagnosis is often neglected when a patient has a proximal walking pain as most doctors evoke a pseudo-claudication. Surprisingly, the management of IIAS is not reported in the Transatlantic Inter-Society II Consensus or in the report of the guidelines of the American College Foundation/American Heart Association. The objectives of this review are to present the current knowledge of the disease, how it should be managed in 2015 and what future research trends are. Lower extremity (LEAD) arterial disease is a highly prevalent disease caused mainly by atherosclerosis, a systemic disease process that alters the normal structure and function of the vessels (). Therefore, the risk factors of LEAD are well identified: non-modifiable risk factors such as age, gender and inheritance; and modifiable risk factors such as smoking, hypertension, diabetes and dyslipemia (). It is common to define proximal LEAD and distal LEAD depending on the ischemia area supplied by the damaged artery (). Twenty to 50% of patients with LEAD are asymptomatic (). When the claudication is present, the distal LEAD is typically characterized by calf pain and is based on common illic lesions and/or external illic arteries and/or femoropopliteal lesions (). Contrary to the distal LEAD, proximal LEAD is characterized by back pains, hips, buttocks or thighs and is based on common and/or isolated internal iliac lesions (, , ).Inner iliac arterial stenosis (IIAS) is one of the possible locations of atherosclerosis in the arterial tree. This disease is often lost in the diagnostic process when a patient has a proximal walking pain. In fact, a pain that appears during walking and involves the lower back, the hip, the buttock or the thigh suggest proximal claudication or proximal pseudoclaudication (). Claudication is a vasculogenic pain while pseudoclaudication results from diseases such as spinal lumbar stenosis, hip osteoarthritis, venous congestion, or bone metastasis, sciatica, etc. (–) (Figure; Table ). Figure 1. Main causes of proximal claudication and pseudoclaudication. Table 1. Differential diagnosis of internal iliac arterial stenosis. Unfortunately, due to almost similar symptoms, vascular origin is largely neglected when a patient has a proximal member pain as most doctors evoke a pseudo-claudication (). A number of explanations may be proposed. First, the claudication was historically defined by a fatigue, discomfort or pain that occurs in the calves during the effort due to exercise-induced ischemia and relieved with rest (). Second, the ankle-brachial index (ABI) is used as standard for the diagnosis of LEAD (). In fact, LEAD is defined by an ABI ≤0.90 (), but the latter may remain within the normal limit in case of gluteal artery lesions isolated () or higher (). Finally, the management of IIAS is not reported in the Transatlantic Inter-Society II (TASC II) or in the report of the guidelines of the American College Foundation/American Heart Association (AHA) (, ).Incidence and Prevalence of IIASIncidence and prevalence of IIAS have not been established in the general population. Although isolated IIAS is probably rare, IIAS is often associated with common iliac arterial stenosis. The prevalence of proximal claudication is 5 to 14% in patients with mild to moderate distal LEAD (, ), high among patients with aortobifemoral patent bypasses (), approximately 28%, and almost 35% of patients after the embolization of the bilateral internal iliac artery (IIA) before the repair of endovascular aneurysm (). Symptoms and functional impairment The main symptom is the lower part of the back, the hip, the buttock or the thigh claudication that defines the proximal claudication, a fatigue, discomfort or pain that occurs in specific muscle groups feeding by IIA during the effort due to exercise-induced ischemia and relieved with rest (, ). However, the presentation of proximal claudication is often atypical and can imitate other non-vascular diseases that can induce misleading diagnoses (, ) (Figure ). In addition, pain may appear at rest when the IIAS is severe, and may lead to even gluteal necrosis (). Finally, IIAS induces different functional deficiencies: the deterioration of walking leading to the disability of work, and the sexual deterioration as erectile dysfunction (, ). These two impediments reduce the patient's quality of life (–). To avoid these impediments, although it is difficult with non-invasive conventional tests, it is of interest to diagnose the disease in order to decrease the delay of diagnosis, which is currently 2 years, when the disease is not associated with distal LEAD (). Strategies and TestsClinical evaluation Patients usually report a gradual decrease in their walking capacity, which is evaluated by maximum walking distance (). Claudication traditionally for within 10 min after the end of walking (, ). The maximum foot distance often harms both with the increase of the arterial stenosis and with the deterioration of the collateral network's functionality, which reduces blood flow to the IIA-released muscles (). The maximum foot distance can be evaluated by different methods: medical interview, questionnaires (), standardized test of running tape that is recommended (), 6-minute test when patients cannot walk on a running tape (), and GPS technology recently (). Physical examination should rule out a pseudo-claudication (). The osteoarthritis of the hip is associated with pain typically in the groin caused by the internal or external rotation of the hip (). The pain of the hip is often radiated on the knee, while spinal lumbar stenosis is associated with discomfort that radiates beyond the spinal zone in the buttocks (). In addition, the active lumbar extension can induce discomfort that is relieved with flexion. Finally, the pain due to bone metastasis is compounded by direct pressure on bones. Different questionnaires have been developed to help doctors distinguish vascular claudication from pseudo-claudication. The most used are the World Health Organization (WHO)/Rose Questionnaire, the Edinburgh Claudication Questionnaire and the San Diego Questionnaire (, , ) [Readers will find these complete questionnaires in the same article published in Vascular Medicine ()]. Pulse palpations, the auscultation of the lower extremities and the abdomen in search of a vascular breath have to be done in the patient (). The measurement of ABI defined as the highest systolic pressure in the pediatric dorsalis or posterior tibial artery divided by the pressure measurement of the higher arm can be useful, although it can be insensitive in the case of isolated internal iliac lesions (, ). It has been suggested that the pressure measurement of the penis be an alternative method to diagnose stenosis (). The brain-penile index (PBI), defined as penis pressure on the relationship of the highest systolic brachyal, is rarely used in routine investigations, and its accuracy is 69.3% (confidence interval of 95%: 58.6–78.7) for the detection of an arterial stenosis or occlusion at least one side compared to arteriograms (). Therefore, a normal PBI (prop.0.60) cannot rule out the presence of injuries in the internal illic arteries (). Classical ImagesThe duplex ultrasound (DUS) of the vascular abdominal circulation can help evoke the diagnosis () (Table). In fact, the sensitivity and specificity of the DUS to assess aorto-iliac disease (stenosis) compared to the arteryography are 91% and 93%, respectively (). However, no study has evaluated the sensitivity and specificity of the DUS in the specific evaluation of the IIAS. Sensitivity and specificity obtained for aorto-iliac disease are probably higher than expected in the IIAS assessment because IIA is deeper and more difficult to evaluate with DUS. Some authors have also suggested indirectly evaluating IIA by studying gluteal artery with DUS, but the results must be confirmed in the larger population (). Table 2. Different tests that can be used to diagnose internal iliac stenosis. Computed-tomodensitometric angiography (CTA) and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA), "semi-invasive" tests can be an option for the diagnosis of IIAS especially when a patient is a candidate for revascularization (Figure ) (Figure ) (). Figure 2. Results of the computed-tomodensitometric angiography: occlusion of the right internal iliac artery. Arrow, occlusion of the right internal iliac artery. Digital subtraction Angiography, an invasive technique remains the gold standard for the diagnosis of IIAS with oblique projections to avoid losing the diagnosis of IIAS (). In fact, the external illic artery hides the IIA at the level of the gluteal channel in antero-posterior views (). On the other hand, as suggested by the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and the AHA, when conducting an arteriogram of lower extremity in which the significance of an obstructive lesion (transstenotic pressure gradient environments) should be obtained. The cut of medium rest gradient to determine whether stenosis is significant is discussed that it goes from 5 () to 10 mm Hg (). The peripheral fractional flow reserve (p-FFR), which is defined as the relation of the distal average pressure with stenosis to the average aortic pressure in hyperemia, could also be a valuable test (–). Functional Evaluation of IIAS during the Outing Both the pressure of transcutaneous exercise oxygen (Exercise-TcPO2) and the exercise of infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) measurements made on running tape have been proposed to estimate the ischemia induced by exercise at the level of buttocks (, , , ). Exercise-TcPO2 reflects skin oxygenation while NIRS reflects muscle oxygenation. However, at least at the level of glutes, the skin and the muscles below are vascularized by the same arterial trunk, the internal artery. Compared to the same study, NIRS and Exercise-TcPO2 provided, respectively, 55% (range, 41.6–67.9%) and 82% (range, 69.6–90.5%) of precision (95% confidence) to predict the presence of arteriographically proven lesions (). Exercise-TcPO2 has sensitivity of 79% and specificity of 86% to detect significant lesions (stenosis ≥75%) in the blood tree of the pelvic circulation when the cutting point is lower then −15 mm Hg () (Figure ). The Exercise-NIRS provides a non-invasive method of measuring the tissue oxygen saturation [StO(2)]. Different parameters have been proposed using different running tape protocols (, , ). Time to 50% of the recovery from StO(2) to the reference base [T(50)] √70 s produced a sensitivity of 89% and a specificity of 85% for PAD (). To predict a significant injury in the arteries to hypogastric circulation, it was considered a recovery time √240 s as a cutting value (). Figure 3. Exercise-TcPO2 procedure in a patient. Case history: a 59-year-old woman, a former hypertension and hyperlipidemia former smoker always reports pain in her right ass when she walks although she had surgery for spinal lumbar stenosis 2 years earlier. The discomfort has worsened progressively in the last 4 months and now forces her to rest after walking 250 m at a normal rate. Pain is interfering with your ability to do your job. It has a normal femoral pulse and a normal ankle-brachial index. (A): patient on a treadmill with five TcPO2 probes (one in each buttock, one in each calf, and one in the chest) and a 12-letter electrocardiogram. High Law (B): TcPO2 probe scheme. Low right (C): typical recordings of Exercise-TcPO2 measurements that show a right buttock ischemia with a DROP (such as the rest of oxygen pressure) less than −15 mm Hg. There is no specific management of IIAS (, ). The medical address is the same as the LEAD. To reduce adverse cardiovascular events such as stroke and acute myocardial infarction, life therapy should include the elimination or modification of atherosclerotic modifiable risk factors such as smoking, hypertension, diabetes mellitus and dyslipidemia (). Daily exercise and favorable diet that limits the atherosclerotic process (, ) is recommended. The indication of revascularization depends on the patient's functional impairment (e.g. normal work or other important activities for the patient) after the lack of adequate response to well-managed exercise therapy and medical treatment (). The morphology of the lesion is also an important criterion for the choice of revascularization (, ).Intervention of lifestyle and atherosclerotic risk factors Modifications The cessation of smoking is needed because it continues to smoke compared to the cessation of smoking. It was found that it increases the risk of death, myocardial infarction and amputation (). Patients who are smokers or former smokers should be asked about the state of tobacco use in each visit and be assisted to stop (). The WHO study group has proposed that guidelines for the prevention of cardiovascular diseases include a low-fat diet (400 g/d for five intakes per day) be encouraged (). Therefore, dietary evaluation should be done in clinical practice with a specific validated tool (). Patients with proximal claudication could benefit from the home-based or supervised training program with at least three sessions of 35 to 45 min per week for a minimum of 12 weeks (, ). Therefore, physical activity must be highly recommended (). Medical Treatment In addition to lifestyle changes, anti-aggregating agents such as aspirin in daily doses of 75 to 325 mg are recommended as safe and effective therapy to reduce the risk of myocardial infarction, stroke and vascular death (). Chlopidogrel (75 mg per day) may be an alternative antiplatelet therapy, as it seems to be more effective than aspirin to prevent ischemic events in patients with LEAD without increasing hemorrhagic events (CEPRIE study) ().We also recommend low-duration drugs for all patients with LDL to achieve a LDL cholesterol goal target less than 100 mg per DL target, and when the risk is high According to these guidelines, in case of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, a high-intensity statin should be used for patients of ≤75 years or a moderate-intensity statin for patients of 75 years of age (). In the heart protection study trial, simvastatin (a hydroxymethyl glutaryl (HMG) coenzyme-A reductase) has significantly reduced the risk of a major vascular event by 22% (confidence interval of 95%: 15–29) in patients with LEAD compared to placebo (). Antihypertensive drugs should be given to patients with LEAD hypertension to achieve a target In diabetic patients, antidiabetic drugs should be given to achieve a goal of Hemoglobin A1c below 7% to reduce microvascular complications and improve cardiovascular outcomes (). Other drugs such as cilostazole or pentoxifylline can be used in patients with LEAD to improve walking distance (). RevascularizationRevascularization can be proposed to patients who have a significant deterioration of walking and after not improving after the medical treatment and supervised exercise training (, ). In the case of isolated IIAS, endovascular treatment is the most used procedure since surgical revascularization is technically more demanding and carries a greater risk for the patient (, ). Contrary to stenosis relative to the common illic artery or the external illic artery, there is no randomized comparison of the placement of primary stent versus percutaneous transluminal angioplasty (PTA) or comparison with the surgery for IIAS (, ). Several studies have evaluated endovascular therapy (single PPT or stenting) in short series of patients. Thompson et al. have shown that the procedures for PTA alone or stent were safe without any complication in nine patients with nalachination: seven out of nine had pain relief after 1 month of follow-up (). Another study, including 21 patients followed during 14.7 ± 5.7 months, found that all patients had a complete relief from the clotting of the glotoco and a significant increase in the walking distance from 85 m to 225 m after the endovascular treatment (PTA alone or stent) (). In 2013, Prince et al. has shown that the endovascular treatment of IIAS has a high rate of technical success (i.e. absence or stenosis after the procedure less than 30%) and a low complication rate (in 3 of 34 patients). In their study (34 patients included), 79% of patients had total or partial relief from the pain of symptoms (). Morse et al., Smith et al., Adlakha et al., and Huetink et al. have also reported different symptomatic cases of IIAS that were successfully treated by endovascular procedures (–). Batt et al. They have also shown good results for angioplasty of the upper lesions of the gluteal artery (, ). Paumier et al. have suggested that in case of common iliac stenosis, aorto-iliac bypasses with a reimplantation of IIA should be discussed (). The same group performed another study in 40 patients, in which a direct revascularization of the IIA was performed to the aorto-iliofemoral bypasses. Proximal claudication after revascularization disappeared in 23 to 27 patients who had previous proximal claudication (). The IIA rate of return was 89% to 1 year and 72.5% to 5 years (). Uncertainty Zones Diagnostic Algorithm To date, no algorithm has been proposed to perform the diagnosis IIAS taking into account the cost of the tests and their possible results to help the diagnosis. Studies on the sensitivity and specificity of several tests such as ultrasound, CTA, or MRA exams are missing in the specific IIAS evaluation. In this case, we propose our diagnostic algorithm (Figure ). Figure 4. Diagnostic algorithm. ABI, ankle-brachial index; Exercise-TcPO2, transcutaneous pressure measurement exercise of oxygen; Exercise-NIRS, infrared spectroscopy; CT scan. Percutaneous Transluminal Angioplasty Alone or Stenting Comparison of primary stent versus angioplasty relative to common illic artery or external artery showed that there were no substantial differences in the technical results and clinical results of the two treatment strategies both in the short and long term (2 years) (). Since the angioplasty followed by selective stent placement is less expensive than the direct placement of a stent, the choice of primary stent or does not have to be studied for IIAS. Evaluation of other atherosclerotic locations An electrocardiogram, carotid and aortic DUS should be discussed because LEAD is associated half the time with other atherosclerotic locations (). Guidelines A specialized multidisciplinary committee organized by ACC and AHA has presented general guidelines for the management of LEAD in 2013 (). Surprisingly, neither this committee nor the TASC II working group mentioned how to manage IIAS (, ). In 2014, the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Intervention (SCAI) has published an expert consensus statement on aorto-iliac arterial management (Aorto-iliac). In this statement, the experts considered:- proper care to treat a patient with moderate symptoms to severe hip clutch buttock or loss of important tissue (Regtherford Classification: 2–6) with IIA ≥50% stenosis and/or rest means translesional gradient ≥5 mm Hg;- may be appropriate care to treat a patient with IAS ≥50% with vasculogen ins. Conclusion This review shows that when a patient has a proximal walking pain, the doctor should look for IIAS. We also find that literature is very low and that guidelines and recommendations need to be addressed to know how to manage IIAS. Conflict of interest The authors state that the investigation was conducted in the absence of commercial or financial relations that could be interpreted as a potential conflict of interest. References 1. Fowkes FG, Rudan D, Rudan I, Aboyans V, Denenberg JO, McDermott MM, et al. Comparison of global prevalence estimates and risk factors for peripheral artery disease in 2000 and 2010: systematic examination and analysis. Lancet (2013) 382(9901):1329–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61249-0382 Silence 2. Hirsch AT, Haskal ZJ, Hertzer NR, Bakal CW, Creager MA, Halperin JL, et al. ACC/AHA 2005 practice guides for the management of patients with peripheral artery disease (lower, renal, mesenterica and abdominal aortics): collaborative report of the American association for surgery/vascular society for vascular surgery, society for angiography and cardiovascular interventions, society for vascular medicine and pulmonary biology, society of interventional radiology, and labor force ACC/AHA Silence 3. Abraham P, Picquet J, Vielle B, Sigaudo-Roussel D, Paisant-Thouveny F, Enon B, et al. Transcutaneous measurements of oxygen pressure in the buttocks during exercise to detect proximal arterial ischemia: comparison with arteryography. Circulation (2003) 107:1896–900. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.0000060500.60646.E0107 Silence 4. Norgren L, Hiatt WR, Dormandy JA, Nehler MR, Harris KA, Fowkes FG. Inter-society Consensus for the Management of Peripheral Artery Disease (TASC II). J Vasc Surg (2007) 45:S5–67. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2006.12.03745 Silence 5. Jaquinandi V, Bouye P, Picquet J, Leftheriotis G, Saumet JL, Abraham P. Pain description in patients with lower blood ischemia of the lower proximal isolated extremity (without distal). Vasc Med (2004) 9:261-5 doi:10.1191/1358863x04vm560oa9 Silence 6. Jaquinandi V, Abraham P, Picquet J, Paisant-Thouveny F, Leftheriotis G, Saumet JL. Estimate of the functional role of the arterial pathways to the circulation of the gluteum during the treadmill walking in patients with claudication. J Appl Physiol (2007) 102:1105-12. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00912.2006102 Silence 7. Katz JN, Harris MB. Clinical practice. Spinal lumbar stenosis. N Engl J Med (2008) 358:818–25. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp0708097358 Silence 8. Lane NE. Clinical practice. Osteoarthritis of the hip. N Engl J Med (2007) 357:1413-21. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp071112357 Silence 9. White C. Clinical practice. Intermittent Claudication. N Engl J Med (2007) 356:1241–50. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp064483356 Silence 10. Bouley JF. Claudication intermittent des membres postérieurs, déterminée par l'oblitération des artères fémorales. Recueil Méd Vét (1831) 8:517–27.8 11. Rooke TW, Hirsch AT, Misra S, Sidawy AN, Beckman JA, Findeiss L, et al. Management of patients with peripheral arterial disease (compilation of 2005 and 2011 ACCF/AHA guidance recommendations): report of the U.S. University of Cardiac Foundation/U.S. Heart Partnership Working Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol (2013) 61:1555–70. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2013.01.00461 Silence 12. Gernigon M, Marchand J, Ouedraogo N, Leftheriotis G, Piquet JM, Abraham P. Proximal ischemia is a frequent cause of pain caused by exercise in patients with normal ankle for the brachial index at rest. Doctor of Pain (2013) 16:57–64.16 Silence 13. Batt M, Baque J, Ajmia F, Cavalier M. Angioplasty of the upper gluteal artery in 34 patients with nalgae claudication. J Endovasc Ther (2014) 21:400–6. doi:10.1583/13-4676R.121 Silence 14. Picquet J, Jaquinandi V, Saumet JL, Leftheriotis G, Enon B, Abraham P. Systematic diagnosis of proximal-sin-distal claudication in a vascular population. Eur J Intern Med (2005) 16:575-9. doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2005.06.01316 Silence 15. Jaquinandi V, Picquet J, Bouyé P, Saumet JL, Leftheriotis G, Abraham P. High prevalence of proximal claudication among patients with aortobifemoral patent patterns. J Vasc Surg (2007) 45:318-8. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2006.09.05045 Silence 16. Rayt HS, Bown MJ, Lambert KV, Fishwick NG, McCarthy MJ, London NJ, et al. Claudication of glutes and erectile dysfunction after the embolization of internal iliac artery in patients prior to the repair of endovascular aortic aneurysm. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol (2008) 31:728-34. doi:10.1007/s00270-008-9319-331 Silence 17. Duff C, Simmen HP, Brunner U, Bauer E, Turina M. Gluteal necrosis after acute ischemia of the internal iliac arteries. Vasa (1990) 19:252-6.19 Silence 18. Karkos CD, Wood A, Bruce IA, Karkos PD, Baguneid MS, Lambert ME. Erectile dysfunction after aortoiliac procedures opened against angioplasty: a surveyed questionnaire. Vasc Endovascular Surg (2004) 38:157–65. doi:10.1177/153857040380020838 Silence 19. McDermott MM, Ades P, Guralnik JM, Dyer A, Ferrucci L, Liu K, et al. Training exercises and resistance in patients with peripheral arterial disease with intermittent claudication and without it: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA (2009) 301:165–74. doi:10.1001/jama.2008.962301 Silence 20. Heidelbaugh JJ. Management of erectile dysfunction. Am Fam Physician (2010) 81:305-12.81 Silence 21. Dumville JC, Lee AJ, Smith FB, Fowkes FG. The quality of life related to the health of people with peripheral arterial disease in the community: the study of the artery of Edinburgh. Br J Gen Pract (2004) 54:826–31.54 Silence 22. Rose GA. Diagnosis of ischemic heart pain and intermittent claudication in field surveys. Bull World Health Organ (1962) 27:645–58.27 Silence 23. Gernigon M, Le Faucheur A, Noury-Desvaux B, Mahe G, Abraham P. Applicability of the global positioning system for the evaluation of the ability to walk in patients with arterial claudication. J Vasc Surg (2014) 60(973–81):e1. doi:10.1016/jvs.2014.04.05360 Silence 24. McDermott MM, Liu K, Guralnik JM, Martin GJ, Criqui MH, Greenland P. Measurement of walking resistance and walking speed with questionnaire: validation of the walking impairment questionnaire in men and women with peripheral arterial disease. J Vasc Surg (1998) 28:1072–81. doi:10.1016/S0741-5214(98)70034-528 Silence 25. Le Faucheur A, Abraham P, Jaquinandi V, Bouye P, Saumet JL, Noury-Desvaux B. Measurement of distance and speed on foot in patients with peripheral arterial disease: a novel method using a global positioning system. Circulation (2008) 117:897-904. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.725994117 Silence 26. Leng GC, Fowkes FG. The Edinburgh claudication questionnaire: an improved version of the WHO/rose questionnaire for use in epidemiological surveys. J Clin Epidemiol (1992) 45:1101–9. doi:10.1016/0895-4356(92)90150-L45 Silence 27. McDermott MM, Greenland P, Liu K, Guralnik JM, Criqui MH, Dolan NC, et al. Leg symptoms in peripheral arterial disease: associated clinical characteristics and functional impairment. JAMA (2001) 286:1599–606. doi:10.1001/jama.286.13.1599286 Silence 28. Criqui MH, Denenberg JO, Bird CE, Fronek A, Klauber MR, Langer RD. The correlation between symptoms and non-invasive results in patients referred to for tests of peripheral arterial diseases. Vasc Med (1996) 1:65–71.1 Silence 29. Inuzuka K, Unno N, Mitsuoka H, Yamamoto N, Ishimaru K, Sagara D, et al. Intraoperative monitoring of the blood flow of the penis and the buttock during repair of an aortic abdominal endovascular aneurysm. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg (2006) 31:359–65. doi:10.1016/j.ejvs.2005.09.01931 Silence 30. Mahe G, Leftheriotis G, Picquet J, Jaquinandi V, Saumet JL, Abraham P. A normal penis pressure cannot rule out the presence of lesions in the arteries that supply hypogastric circulation in patients with arterial claudication. Vasc Med (2009) 14:331-8. doi:10.1177/1358863X0910617314 Silence 31. Currie IC, Jones AJ, Wakeley CJ, Tennant WG, Wilson YG, Baird RN, et al. Non-invasive aortoiliac evaluation. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg (1995) 9:24-8. doi:10.1016/S1078-5884(05)80220-59 Silence 32. Bruninx G, Salame H, Wery D, Delcour C. [Doppler study of gluteal arteries. A useful tool to exclude gluteal arterial pathology snd an important joint for lower-member Doppler studies]. J Mal Vasc (2002) 27:12-7.27 Silence 33. Hassen-Khodja R, Batt M, Michetti C, Le Bas P. Radiological anatomy of the anastomtic systems of the internal illogical artery. Surg Radiol Anat (1987) 9:135–40. doi:10.1007/BF020865989 Silence 34. Klein AJ, Feldman DN, Aronow HD, Gray BH, Gupta K, Gigliotti OS, et al. SCAI expert consensus statement for aorto-iliac arterial intervention appropriate use. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv (2014) 84:520-8. doi:10.1002/ccd.2550584 Silence 35. Tetteroo E, van der Graaf Y, Bosch JL, van Engelen AD, Hunink MG, Eikelboom BC, et al. Random comparison of primary stent placement against primary angioplasty followed by selective stent placement in patients with iliac-artery occlusive disease. Dutch iliac stent trial study group. Lancet (1998) 351:1153–9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(97)09508-1351 Silence 36. Hioki H, Miyashita Y, Miura T, Ebisawa S, Motoki H, Izawa A, et al. Diagnostic value of the peripheral fractional flow reserve in isolated iliac stenosis: a comparison with the post-exercise ankle-brachial index. J Endovasc Ther (2014) 21:625–32. doi:10.1583/14-4734MR.121 Silence 37. Jaquinandi V, Kaladji A, Lederlin M, Mahe G. Re: "diagnostic value of the peripheral fractional flow reserve in isolated iliac stenosis: a comparison with post-exercise ankle-brachial index". J Endovasc Ther (2015) 22:272-4. doi:10.1177/152660281557609322 Silence 38. Tonino PA, De Bruyne B, Pijls NH, Siebert U, Ikeno F, van't Veer M, et al. Fractional flow reserve versus angiography for percutaneous coronary intervention. N Engl J Med (2009) 360:213–24. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0807611360 Silence 39. Sugano N, Inoue Y, Iwai T. Assessment of the clouting of buttocks with measurement of hypogastric blood pressure and near infrared spectroscopy after repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg (2003) 26:45–51. doi:10.1053/ejvs.2002.187026 Silence 40. Mahe G, Kalra M, Abraham P, Liedl DA, Wenberg PW. Application of transcutaneous oxygen pressure measurements for detection of proximal lower extremity arterial disease: a case report. Vasc Med (2015) 20:251-5 doi:10.1177/1358863X1456703020 Silence 41. Bouye P, Jacquinandi V, Picquet J, Thouveny F, Liagre J, Leftheriotis G, et al. Infrared spectroscopy and transcutaneous pressure of oxygen during exercise to detect blood ischemia at the level of blood cells: compared to arteryography. J Vasc Surg (2005) 41:994-9. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2005.03.02041 Silence 42. Comerota AJ, Throm RC, Kelly P, Jaff M. Tissue (muscle) oxigen saturation (StO2): a new measure of low-extremetic arterial disease. J Vasc Surg (2003) 38:724-9. doi:10.1016/S0741-5214(03)01032-238 Silence 43. Ubbink DT, Koopman B. Nearby infrared spectroscopy in routine diagnostic work of patients with leg ischemia. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg (2006) 31:394–400 doi:10.1016/j.ejvs.2005.10.02531 Silence 44. Jonason T, Bergstrom R. Cessation of smoking in patients with intermittent claudication. Effects on the risk of peripheral vascular complications, myocardial infarction and mortality. Acta Med Scand (1987) 221:253–60. doi:10.1111/j.0954-6820.1987.tb00891.x221 Silence WHO. Recommendations for the prevention of cardiovascular diseases: Guidelines for the evaluation and management of cardiovascular risk. Geneva: World Health Organization (2007). 46. Carsin-Mahe M, Abraham P, Le Faucheur A, Leftheriotis G, Mahe G. Simple routine evaluation of the dietary pattern in patients with peripheral arterial disease. J Vasc Surg (2012) 56:281–2. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2012.02.05956 Silence 47. Gardner AW, Parker DE, Montgomery PS, Scott KJ, Blevins SM. Effectiveness of quantitative exercise based on the home and exercise supervised in patients with intermittent claudication: a randomized controlled trial. Circulation (2011) 123(5):491–8. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.963066123 Silence 48. Collaboration of Antitrombotic Judgments. Collaborative meta-analysis of randomized anti-aggregating therapy trials for death prevention, myocardial infarction and stroke in high-risk patients. BMJ (2002) 324:71–86. doi:10.1136/bmj.324.7329.71324 Silence 49. Board of Directors of CAPRIE. A randomized, blind, chlorpidogrel trial against aspirin in patients at risk of ischemic events (CAPRIE). CAPRIE Steering Committee. Lancet (1996) 348:1329–39. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(96)09457-3348 Silence 50. Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, Bairey Merz CN, Blum CB, Eckel RH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA directline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American college of cardiology/American heart association task force on practice guidelines. Circulation (2014) 129:S1–45. doi:10.1161/01.cir.0000437738.63853.7a129 Silence 51. Heart Protection Study Collaborative Group. Random test of the effects of cholesterol reduction with simvastatin on peripheral vascular results and other major vasculars in 20,536 people with peripheral arterial disease and other high-risk conditions. J Vasc Surg (2007) 45:645-54. doi:10.1016/jvs.2006.12.05445 Silence 52. Yusuf S, Sleight P, Pogue J, Bosch J, Davies R, Dagenais G. Effects of angiotensin-converting-enzymehibitor, ramipril, on cardiovascular events in high-risk patients. Researchers of cardiac results assessment study. N Engl J Med (2000) 342:145–53. doi:10.1056/NEJM200001203420301342 Silence 53. Ahimastos AA, Walker PJ, Askew C, Leicht A, Pappas E, Blombery P, et al. Effect of ramipril in walking times and quality of life among patients with peripheral arterial disease and intermittent claudication: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA (2013) 309:453–60. doi:10.1001/jama.2012.2162309 Silence 54. Thompson K, Cook P, Dilley R, Saeed M, Knowles H, Terramani T, et al. Angioplasty and internal iliac artery stent: an underused therapy. Ann Vasc Surg (2010) 24:23–7. doi:10.1016/j.avsg.2009.05.00524 Silence 55. Donas KP, Schwindt A, Pitoulias GA, Schonefeld T, Basner C, Torsello G. Endovascular treatment of obstructive disease of the internal iliac artery. J Vasc Surg (2009) 49:1447–51. doi:10.1016/j.jvs.2009.02.20749 Silence 56. Picquet J, Miot S, Abraham P, Venara A, Papon X, Fournier HD, et al. Cross retroperitoneal approach of the internal iliac artery: preliminary anatomical study. Surg Radiol Anat (2006) 28:180-4. doi:10.1007/s00276-005-0066-828 Silence 57. Prince JF, Smits ML, van Herwaarden JA, Arntz MJ, Vonken EJ, van den Bosch MA, et al. Endovascular treatment of internal iliac arterial stenosis in patients with nalga clutration. PLoS One (2013) 8:e73331. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.00733318 Silence 58. Huetink K, Steijling JJ, Mali WP. Endovascular treatment of internal iliac artery in peripheral arterial disease. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol (2008) 31:391-3. doi:10.1007/s00270-006-0106-831 Silence 59. Adlakha S, Burket M, Cooper C. Percutaneous intervention for the total chronic occlusion of the internal iliac artery for the incessant claudication of buttocks. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv (2009) 74:257–9. doi:10.1002/ccd.2196674 Silence 60. Morse SS, Cambria R, Strauss EB, Kim B, Sniderman KW. Transluminal angioplasty of the hypogastric artery for the treatment of nailing. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol (1986) 9:136-8. doi:10.1007/BF025779229 Silence 61. Smith G, Train J, Mitty H, Jacobson J. Hip pain caused by buttock claudication. Relief of symptoms by transluminal angioplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res (1992):176–80. Silence 62. Batt M, Baque J, Bouillanne PJ, Hassen-Khodja R, Haudebourg P, Thevenin B. Percutaneous angioplasty of the upper gluteal artery for the cloudication of buttocks: a report of seven cases and literature review. J Vasc Surg (2006) 43:987–91. doi:10.1016/jvs.2006.01.02443 Silence 63. Paumier A, Abraham P, Mahe G, Maugin E, Enon B, Leftheriotis G, et al. Functional result of hypogastric revascularization for the prevention of blood cell claudication in patients with occlusive disease of peripheral artery. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg (2010) 39:323-9. doi:10.1016/j.ejvs.2009.10.00939 Silence 64. Maugin E, Abraham P, Paumier A, Mahe G, Enon B, Papon X, et al. Patency of direct revascularization of hypogastric arteries in patients with occlusive aortoiliac disease. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg (2011) 42:78–82. doi:10.1016/j.ejvs.2011.03.01442 Silence 65. Steg PG, Bhatt DL, Wilson PW, D'Agostino R Sr., Ohman EM, Rother J, et al. One-year cardiovascular event rates in external patients with aterotrombosis. JAMA (2007) 297:1197–206. doi:10.1001/jama.297.11.1197297 Silence Keywords: stenosis, management, methods, surgery, peripheral artery disease Cytation: Mahé G, Kaladji A, Le Faucheur A and Jaquinandi V (2015) Internal iliac stenosis: diagnosis and how to manage it in 2015. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2:33. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2015.00033 Received: 08 April 2015; Accepted: 18 August 2015; Published: 01 September 2015 Edited by:Reviewed by: Copyright: © 2015 Mahé, Kaladji, Le Faucheur and Jaquinandi. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the . It is permitted to use, distribute or reproduce in other forums, provided that the author or the original licensor is credited and that the original publication is cited in this journal, in accordance with the accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted that does not comply with these terms. *Correspondence: Guillaume Mahé, Pôle Imagerie et Explorations Fonctionnelles, CHU Pontchaillou, Rennes, 2 avenue Henri Le Guilloux, Cedex 9 35033, France, maheguillaume@yahoo.fr

Accessibility links Search results Common iliac artery toxic Radiology Reference Article ...L) Arterias de la Pelvis - OzRadOncTutorial 28: how to remember the branches of the internal iliac ... Internal iliac artery (mnemonic) peru Radiology ... Internal artery of Iliac - YouTubeGross anatomy - Drawing the branches of iliac arteries ... Branches and Clinical Points _ KenhubCongenital Absence of the Right Common Iliac ArteryNovel, congenital iliac artery anatomy: Absent common iliac ... inner ilic artery: toxic anatomy KenhubPage navigation1 Foot links

Common iliac artery - Wikipedia

Iliac Artery - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics

iliac arteries:background_color(FFFFFF):format(jpeg)/images/library/12623/Common_iliac.png)

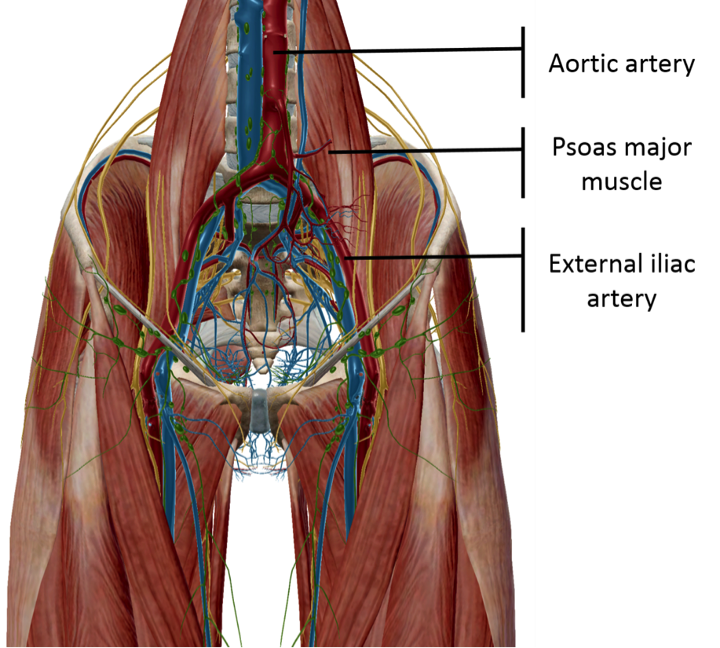

Iliac arteries: Branches and clinical points | Kenhub

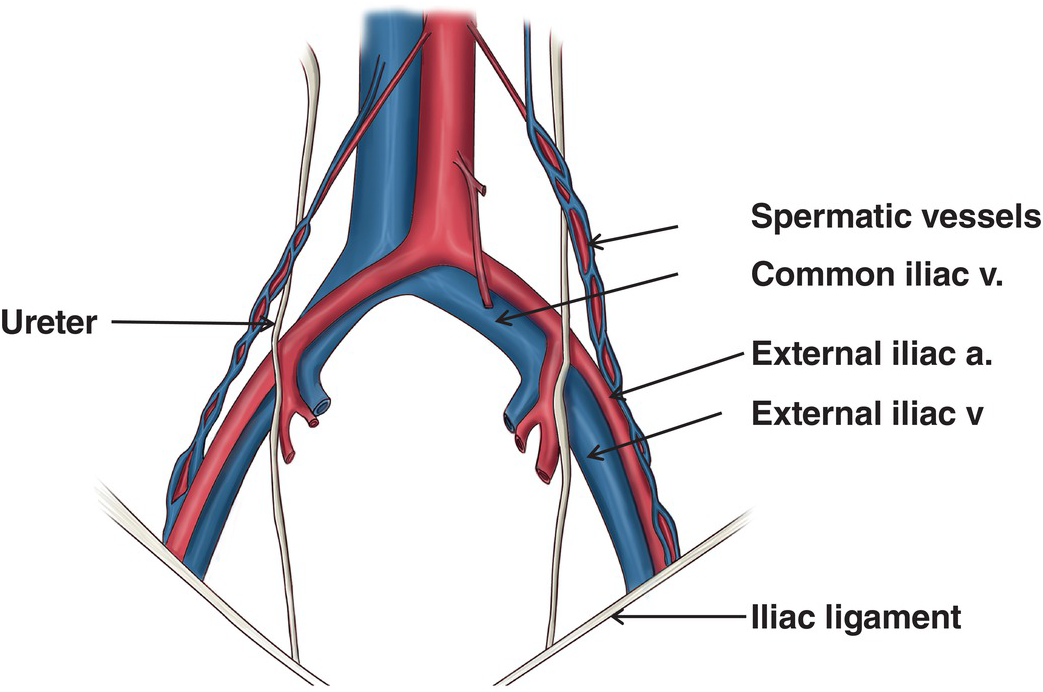

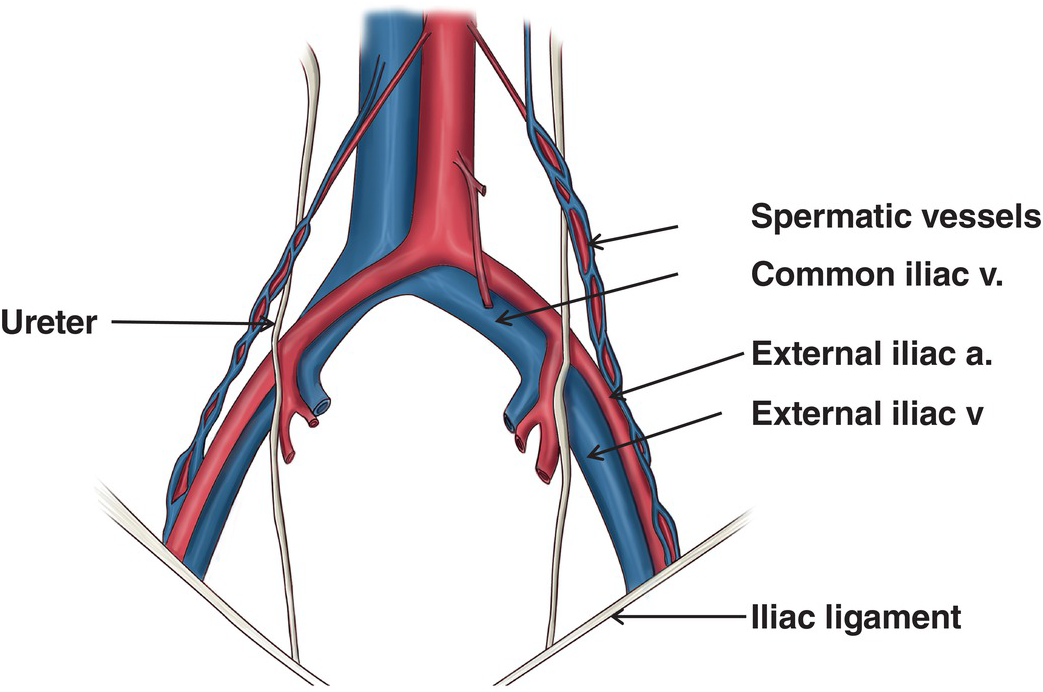

Iliac vessels | Musculoskeletal Key

Frontiers | Internal Iliac Artery Stenosis: Diagnosis and How to Manage it in 2015 | Cardiovascular Medicine

Iliac Vessel Injuries (Chapter 32) - Atlas of Surgical Techniques in Trauma

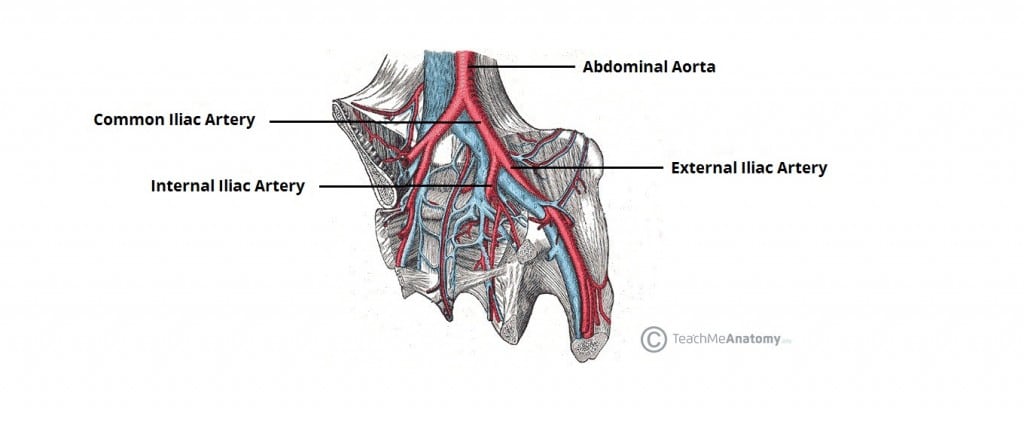

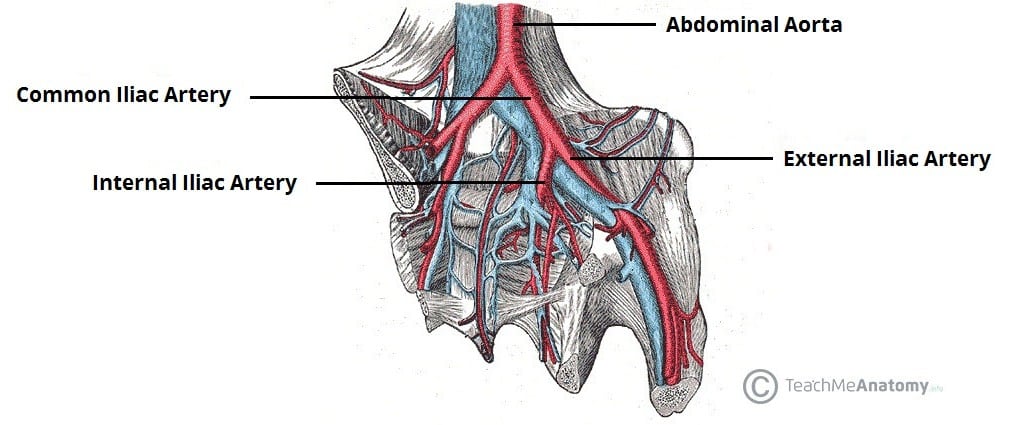

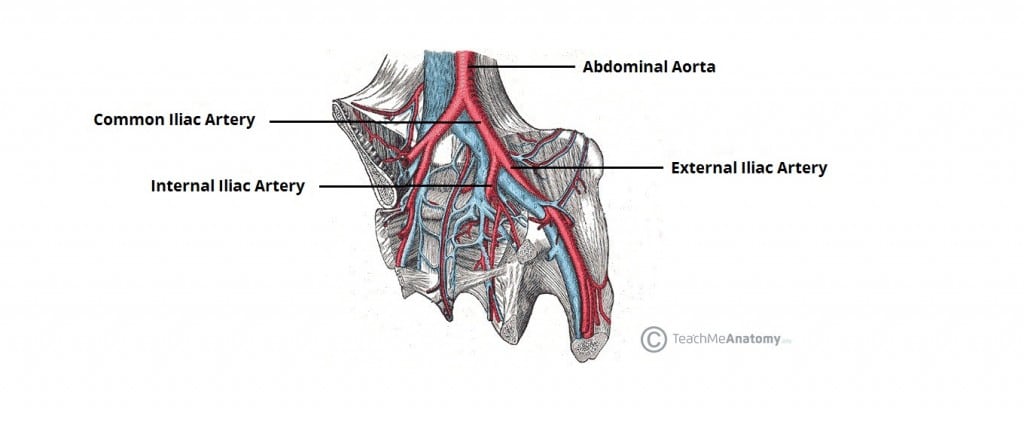

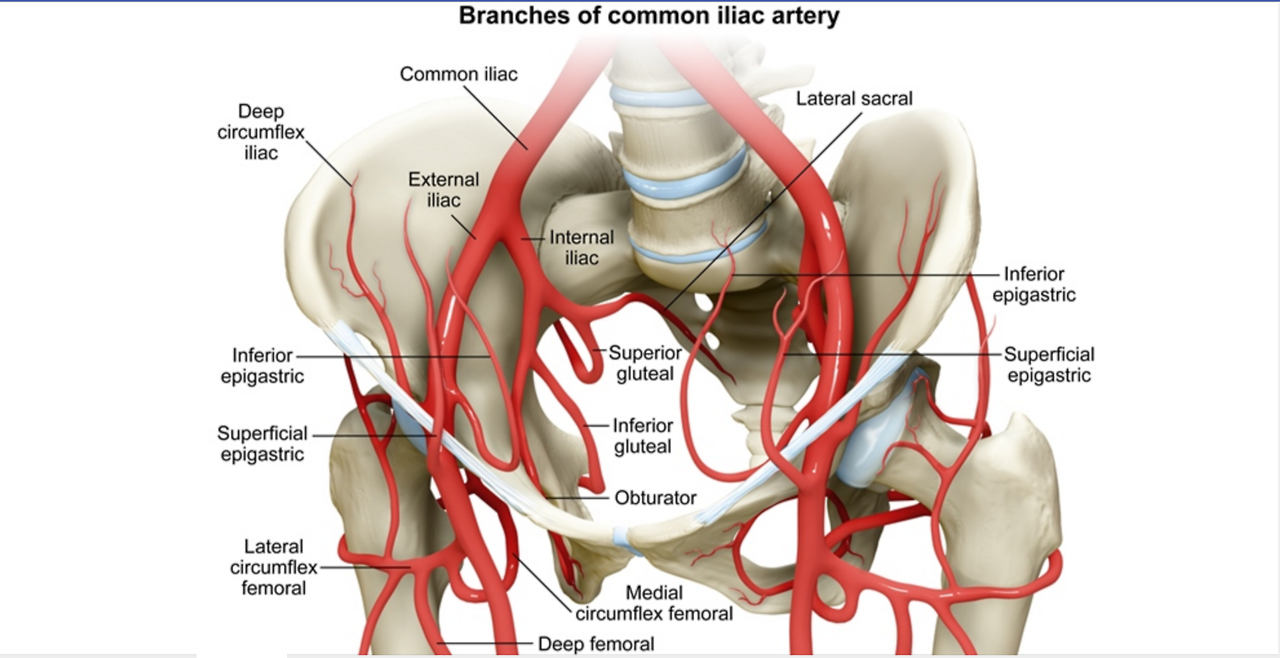

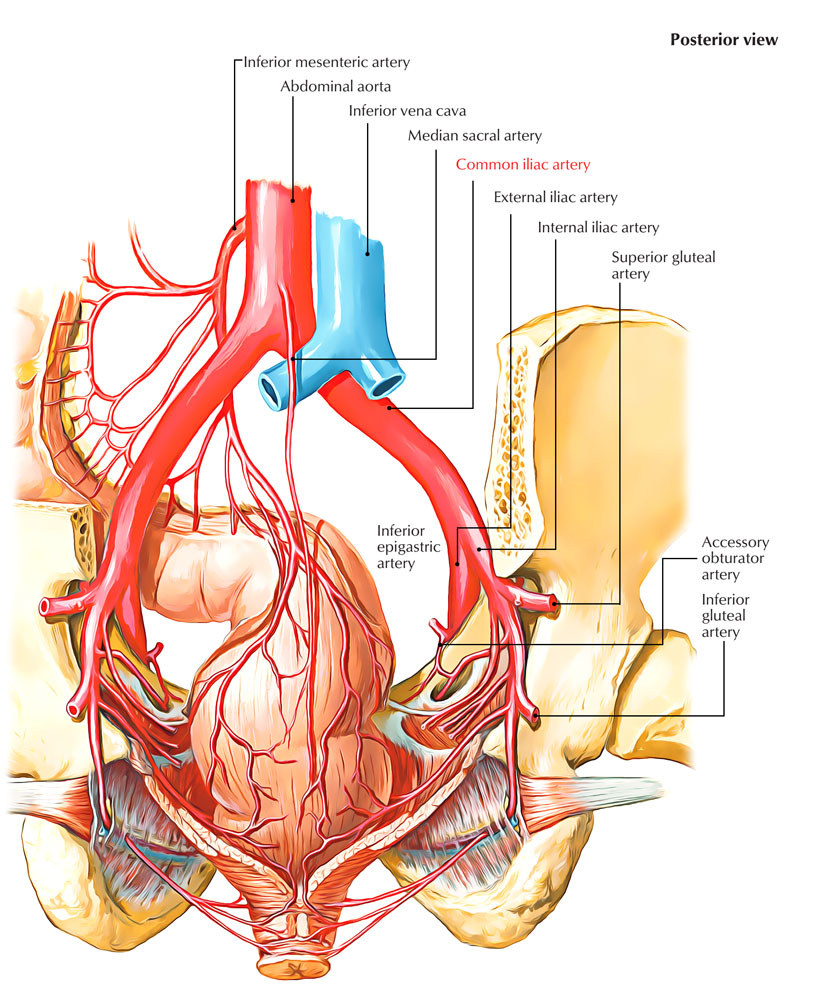

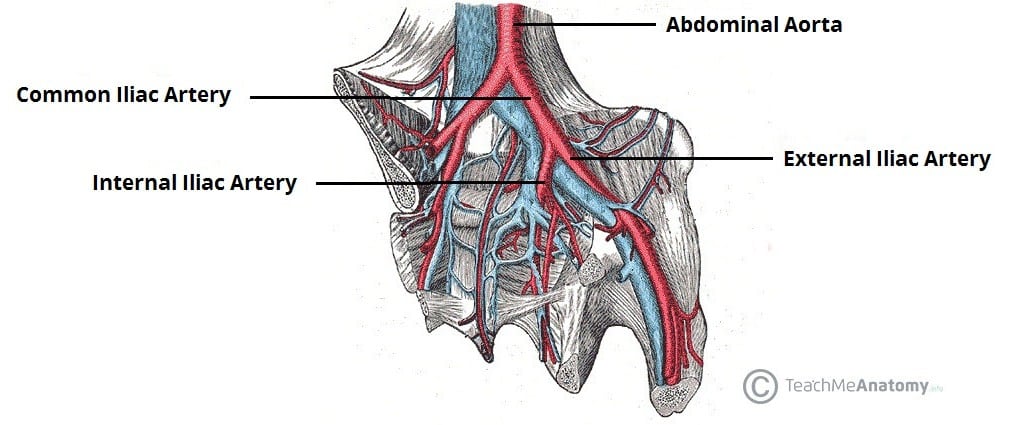

Arteries of the Pelvis - Internal Iliac - Pudendal - Vesical - TeachMeAnatomy

Tutorial 28: how to remember the branches of the internal iliac artery | Sauropod Vertebra Picture of the Week

USMLE Notes — Branches of the iliac artery. Most important...

Easy Notes On 【Common Iliac Arteries】Learn in Just 3 Minutes! – Earth's Lab

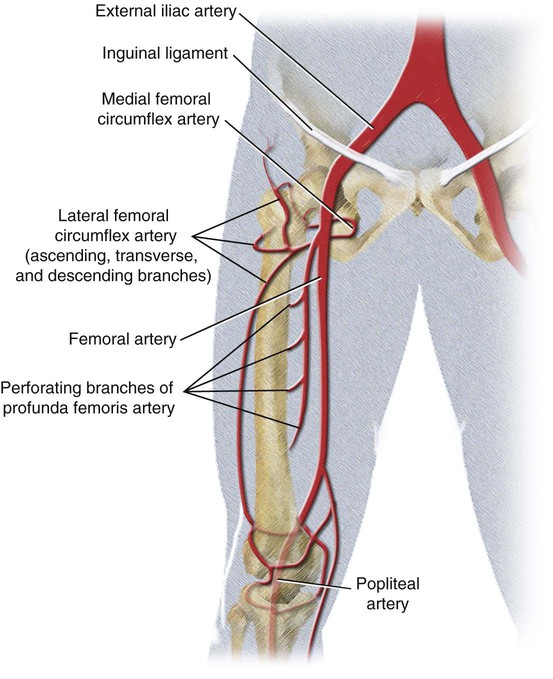

External Iliac Artery (Course + Branches) - YouTube

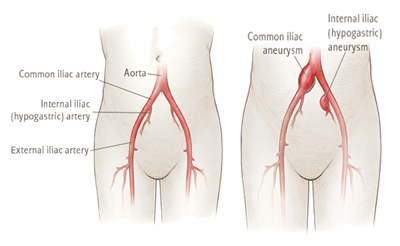

Iliac Artery Aneurysm NJ & PA | Cooper University Health Care

Study of the utility and problems of common iliac artery balloon occlusion for placenta previa with accreta - Ono - 2018 - Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Research - Wiley Online Library:background_color(FFFFFF):format(jpeg)/images/article/en/external-iliac-artery/icmHAe5gwDF9djOEVRTP3w_25EYcjhKfYuAdkdOqZMvw_A._iliaca_externa_02.png)

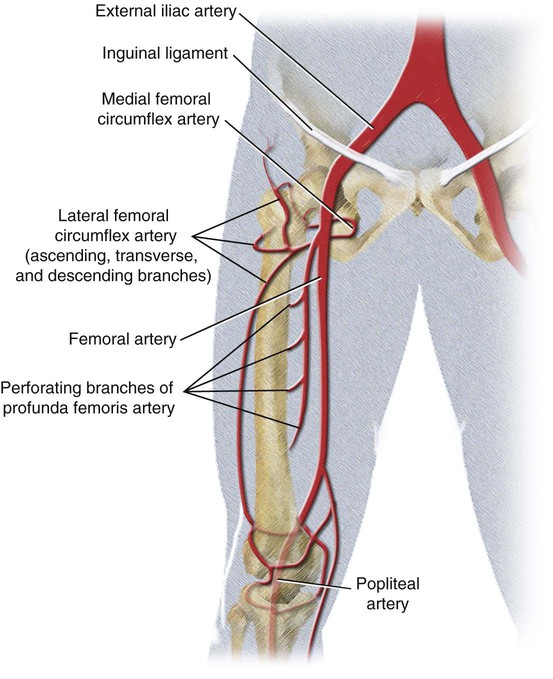

External iliac artery: Anatomy and branches | Kenhub

Common Iliac Artery - Stepwards

Iliac injuries (Chapter 29) - Atlas of Surgical Techniques in Trauma

Iliac Artery - an overview | ScienceDirect Topics

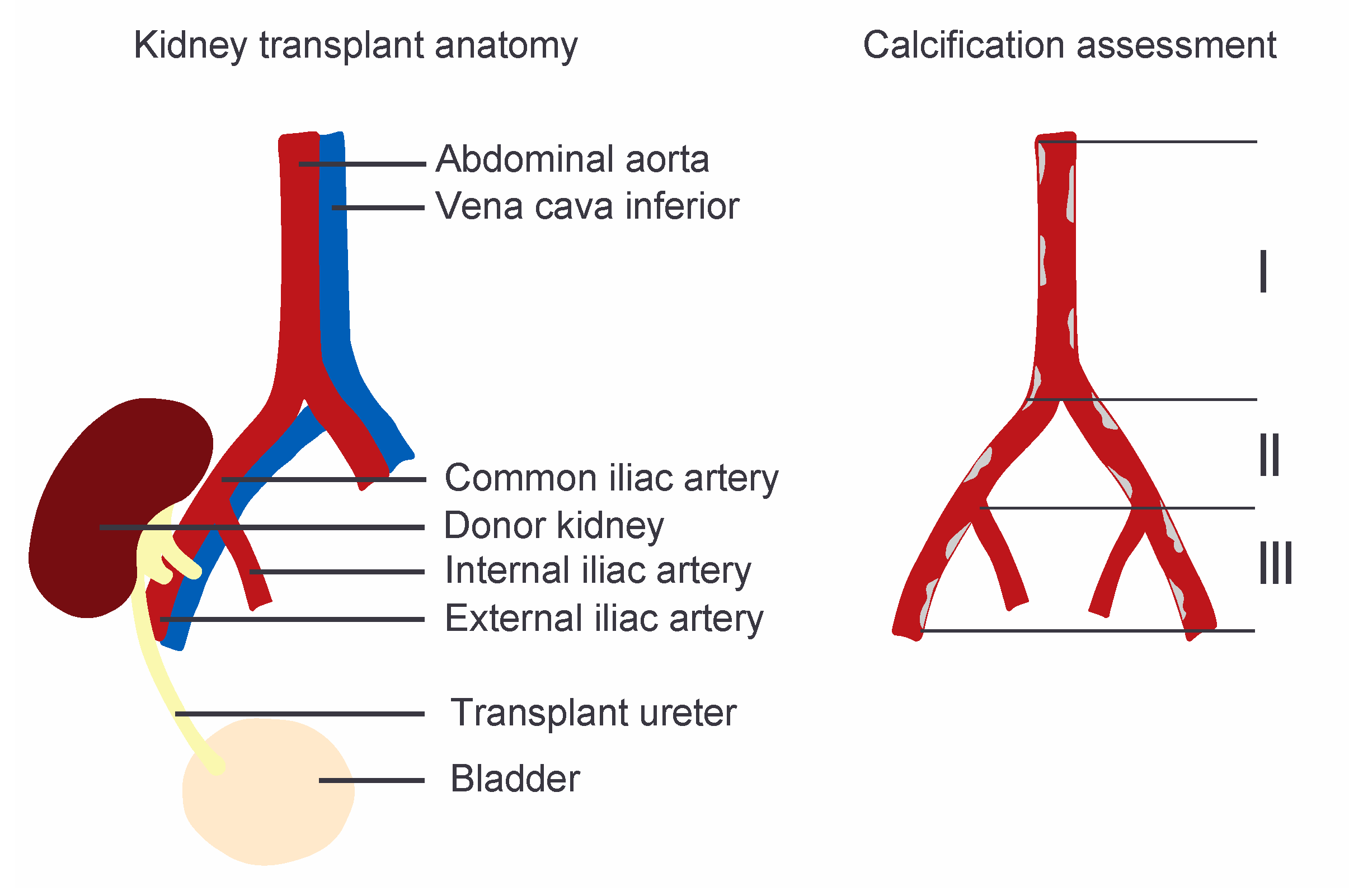

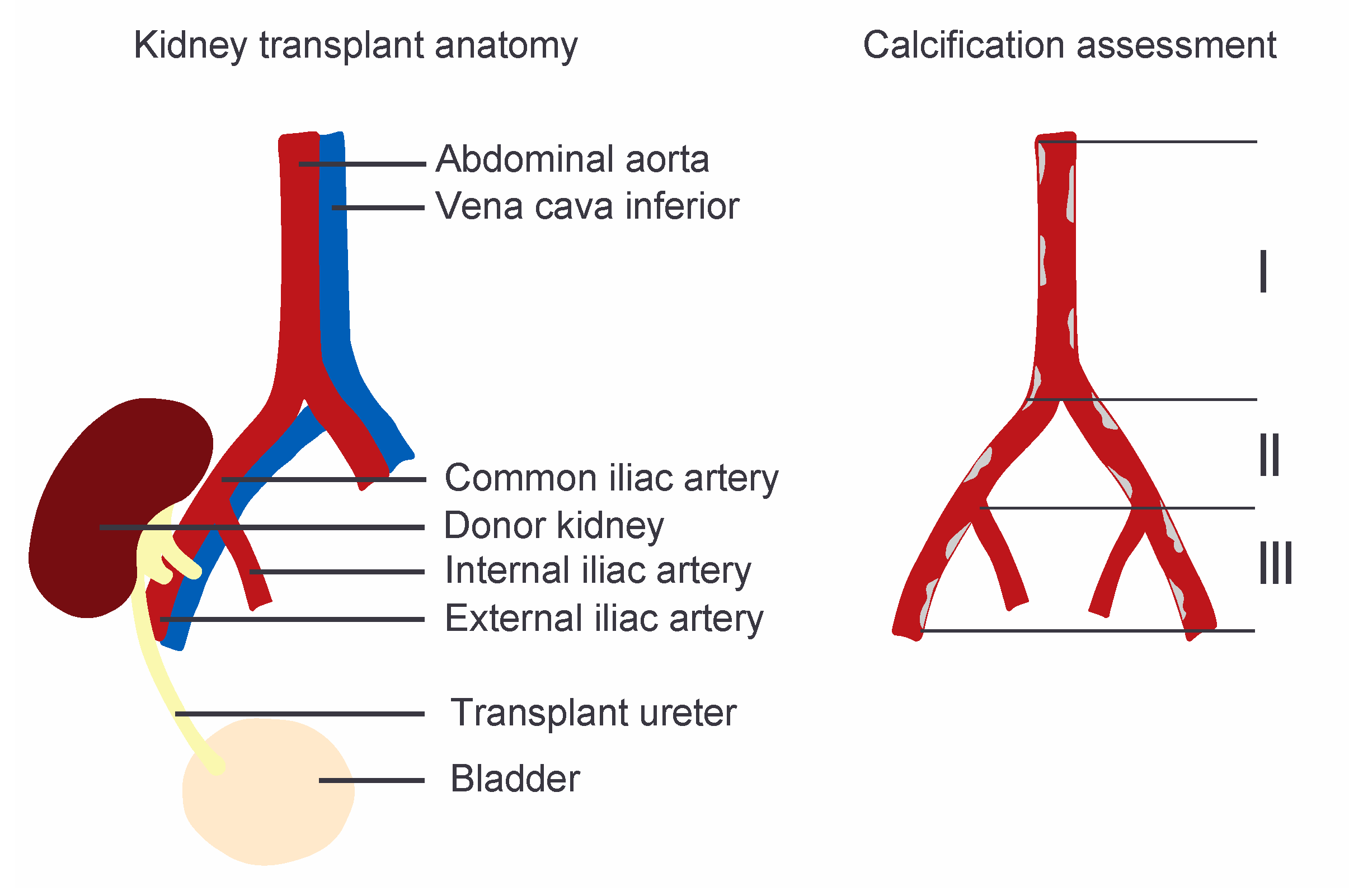

JCM | Free Full-Text | Aorto-Iliac Artery Calcification Prior to Kidney Transplantation:background_color(FFFFFF):format(jpeg)/images/article/en/common-iliac-artery/5KntKg6REfp3ZGH588xoFQ_Ca4EPJ42qNOFSNQadWUcyQ_A._iliaca_communis_m01.png)

Common iliac artery: Anatomy, branches, supply | Kenhub

Arteries of the Pelvis - Internal Iliac - Pudendal - Vesical - TeachMeAnatomy

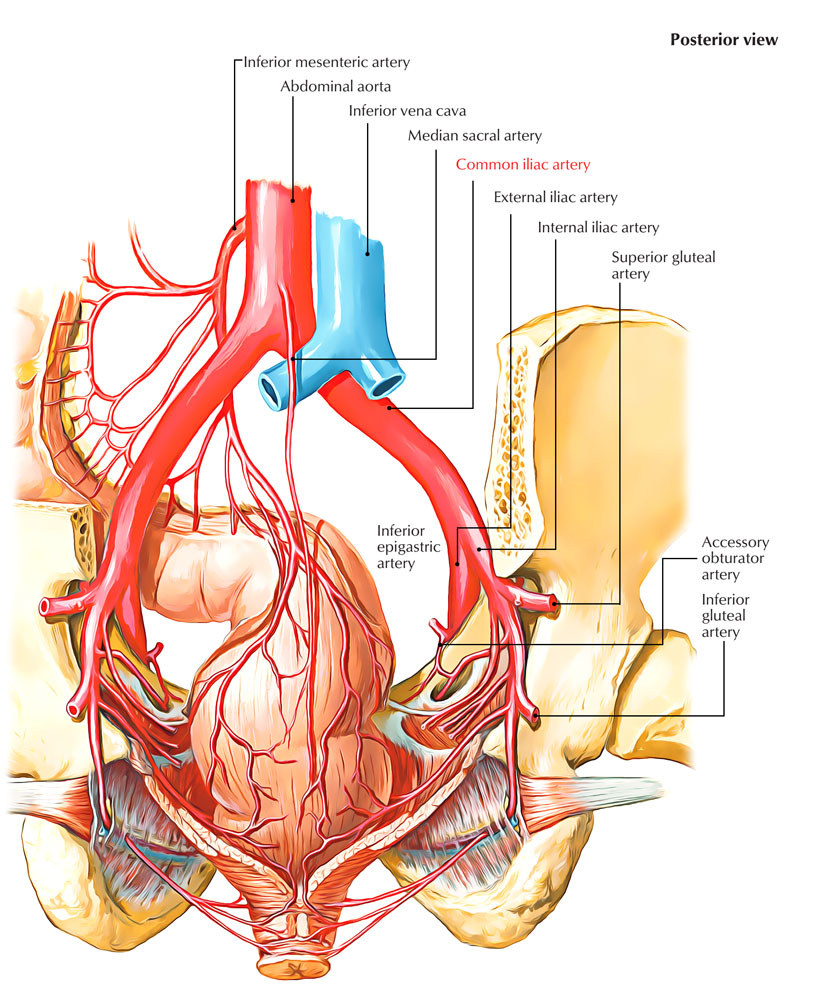

Vascular Anatomy of the Pelvis | Radiology Key

Aorta & Iliac Artery Disease

Hybrid Open Endovascular Repair of Para-Anastomotic Common Iliac Artery Aneurysm in the Presence of Bilateral External Iliac Artery Occlusions - Annals of Vascular Surgery

Internal Iliac Artery | Radiology Key

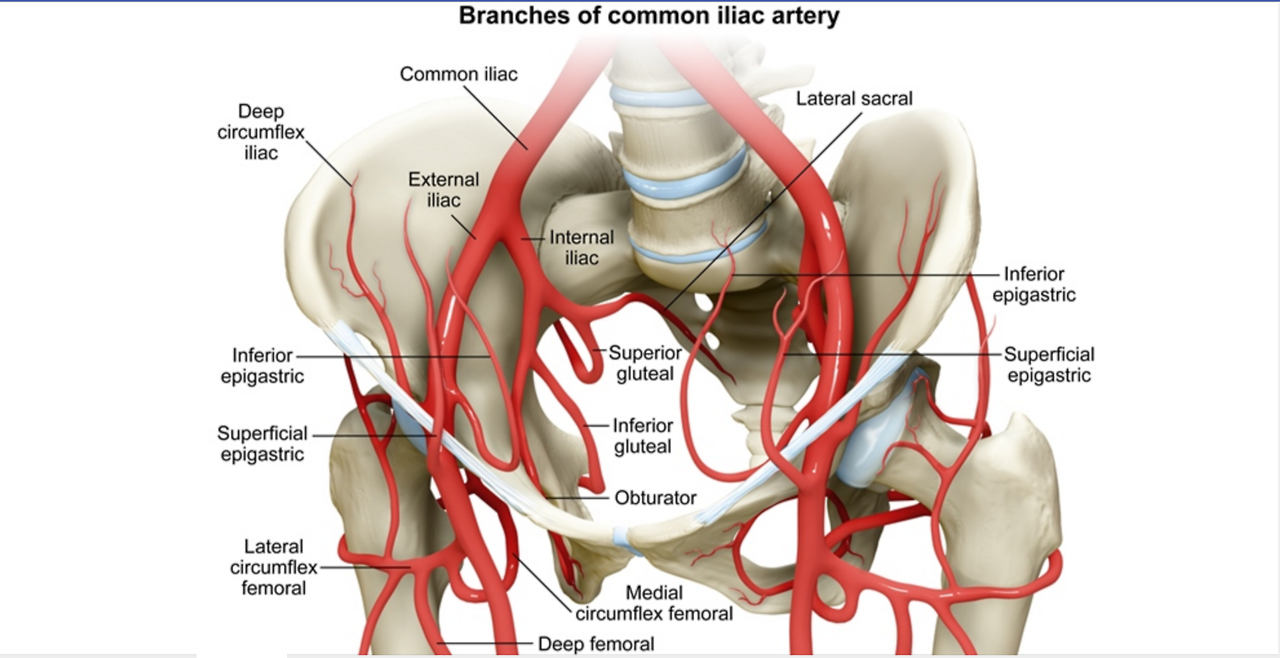

Branches of Internal Iliac Artery | The Lecturio Medical Online Library

Easy Notes On 【Internal Iliac Artery】Learn in Just 3 Minutes! – Earth's Lab

Common Iliac Artery: Anatomy, Topography, Course, Branches, 3D Anatomy

What is Iliac Vein Compression Syndrome? | DFW | HeartPlace

Uncommon injuries: external iliac artery endofibrosis

393 Iliac Artery Photos and Premium High Res Pictures - Getty Images

Iliac Artery Stent

Internal Iliac Artery / Hypogastric Artery - YouTube

Morphology and Hemodynamics in Isolated Common Iliac Artery Aneurysms Impacts Proximal Aortic Remodeling | Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology

Cyclist's (or Athlete's) Iliac Artery Syndrome – Could you or someone you know be a sufferer? — Steemit

Research Review: Endofibrosis Of The Iliac Arteries - Medicine Of Cycling

Transradial Intervention of a Chronic Total Iliac Artery Occlusion | Cath Lab Digest

Branches of the Internal and External ILIAC ARTERIES - YouTube

Breakdown of the study subjects. CIABO, common iliac artery balloon... | Download Scientific Diagram

Volume Change after Endovascular Treatment of Common Iliac Arteries ≥ 17 mm Diameter: Assessment of Type 1b Endoleak Risk Factors - European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery

:background_color(FFFFFF):format(jpeg)/images/library/13435/Ca4EPJ42qNOFSNQadWUcyQ_A._iliaca_communis_m01.png) Common iliac artery: Anatomy, branches, supply | Kenhub

Common iliac artery: Anatomy, branches, supply | Kenhub

:background_color(FFFFFF):format(jpeg)/images/library/12623/Common_iliac.png)

:background_color(FFFFFF):format(jpeg)/images/article/en/external-iliac-artery/icmHAe5gwDF9djOEVRTP3w_25EYcjhKfYuAdkdOqZMvw_A._iliaca_externa_02.png)

:background_color(FFFFFF):format(jpeg)/images/article/en/common-iliac-artery/5KntKg6REfp3ZGH588xoFQ_Ca4EPJ42qNOFSNQadWUcyQ_A._iliaca_communis_m01.png)

Posting Komentar untuk "where is the iliac artery"